Chocolate for the Table: How Taza Transforms a Mexican Drink Into a Bar With Bite

Owner Alex Whitmore carving patterns into a stone for grinding chocolate

The Eskimos may have 50 words for snow, but I’d much rather be a Mayan, since they had lots of different words for chocolate, in all of its many forms. My favorite is chokola’j: “to drink chocolate together.”

Because for most of its life, chocolate has been a drink. In Central and South America, it was a savory, spicy, hot beverage mixed with corn, chiles, and all sorts of spices, then beaten until it was frothy and served to royals. Europeans and North Americans used to drink it alongside their tea and coffee in bitter form too, while they talked philosophy and politics (if history had gone differently, it could have been the Boston Chocolate Party instead of the Boston Tea Party).

But the idea of eating chocolate — well, that’s new. Joseph Fry discovered how to make it into a solid back in 1847, and since then, we Americans have never looked back.

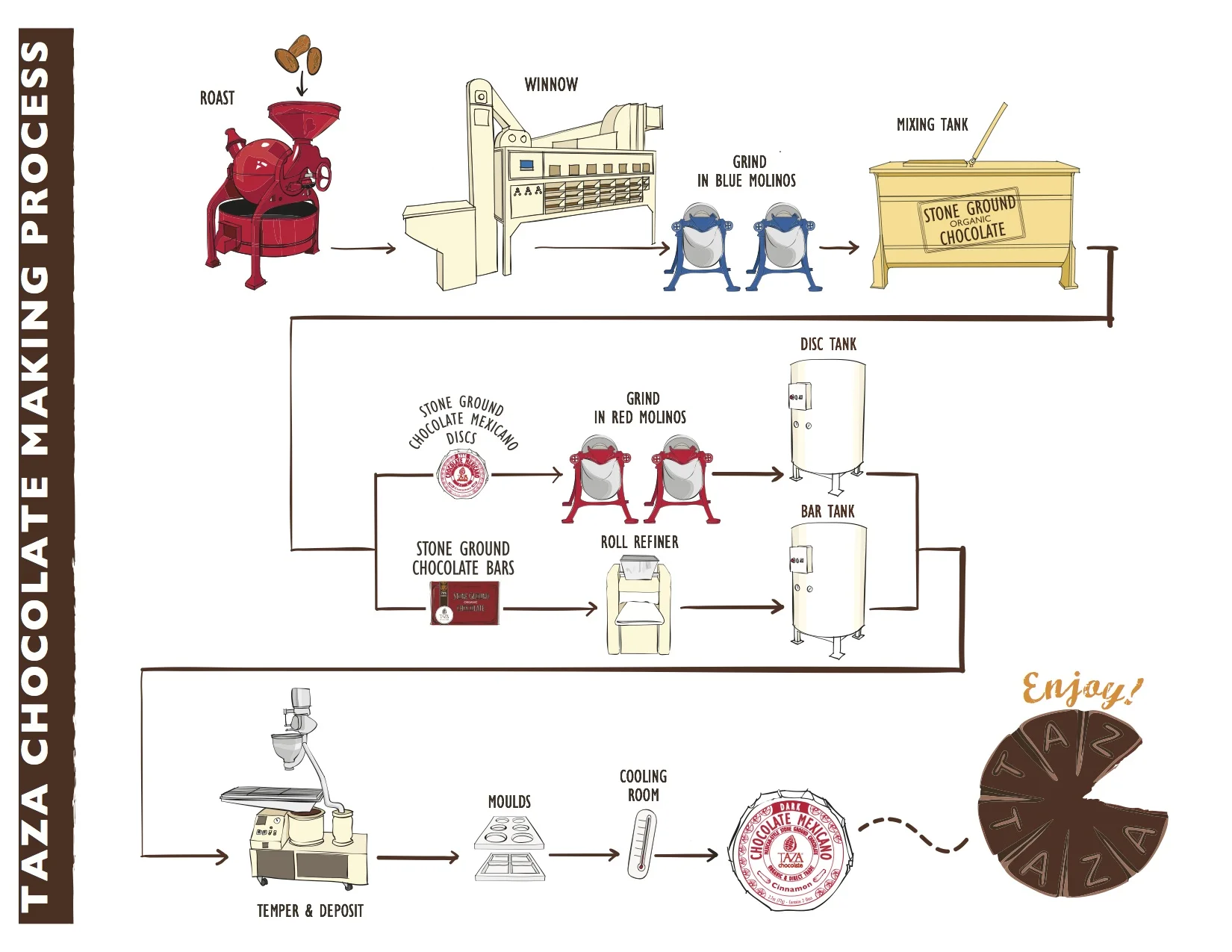

All of us except for Taza Chocolate, that is. Taza makes stone-ground eating chocolate in the Mexican tradition: In Mexico, most people still drink their chocolate. They grind it roughly using a metate and add in things like sugar, almonds, and spices, then drop the tablets into hot water and drink it down.

A traditional metate; photo courtesy Flickr user Omar Bárcena

“I was totally enamored by that idea,” CEO and founder Alex Whitmore told me. “That chocolate doesn’t have to be this European traditional waxy smooth confection, that it’s more than that.”

In the early 2000s, he had decided to start a bean-to-bar chocolate company, taking a nod from companies like Scharffen Berger, Dagoba, and Joseph Schmidt Confections (which, by the way, were all later bought out by Hershey). “It was inspirational,” he said, “because it was a new way of thinking about business in the chocolate and confection industry.” But he didn’t know what that chocolate was going to look or taste like, so in 2005 he headed from Boston to Oaxaca to try some Mexican chocolate and find more inspiration.

“I was blown away by seeing these rudimentary stone mills used to grind roasted cocoa beans into fine liquor and then mixed with sugar into this chocolate para mesa, ‘chocolate for the table’” he told me. He’d found his process.

But it wasn’t that easy. The rotary stones are carved with intricate patterns that are the work of an individual mill worker, or molinero. And they’ll be damned if they give away their trade secrets. If you try to apprentice with one of them, “they look at you like, ‘Who is this gringo?!’” Alex explained. Molineros traditionally pass the methods for “dressing” the stones (carving the patterns) from father to son (they’re rarely women), and it’s hard to penetrate that inner circle. In fact, when it’s time to repair the stones, molineros will even take them off the mill and go somewhere private to fix them!

Why it is such a big deal? Each ingredient (chocolate, sugar, corn, and so on) needs a different stone with a different pattern, and one tiny error in the pattern can totally alter the result. “If we were to pass a sugared mass through the [chocolate] liquor molinos,” Alex said, “it would fill the room with smoke, and the whole thing would caramelize.”

Alex eventually convinced a molinero named Carlos to show him some basic techniques, for example how to carve the flower-like pattern into a flat stone using a hammer and chisel, as well as how to delicately re-carve the patterns as they wear down, about every 14 weeks. “He offered the basics only,” Alex said, noting that he learned most everything he knows from books and trial and error.

Eventually he came up with a process that works, using chocolate from Belize, the Dominican Republic, and Bolivia (Mexico doesn’t export enough chocolate to make it practical).

Courtesy of Taza Chocolate/Kathleen Fulton

The result is an eating chocolate that is unlike anything else in the U.S.: grainy, sweet, distinct. Taza altered the traditional recipe a bit for an American audience so that we can eat the stuff in solid form, but you can still make a pretty traditional chocolate drink by grating the chocolate and whisking it into hot milk or water. Back in the day, the Aztecs and Mayans thought the frothier the beverage, the better. They used a tool called a molinillo to stir up the stuff, but if you wanted it really good and frothy, you’d pour it from one jug into another from a pretty significant height; as the liquid fell a few feet and then splashed into the bottom jug, it would become frothier and frothier. Do that a few times and it might be ready to serve to Montezuma.

Alex and his team decided to give the bars their distinct round shape to honor those traditions. “We didn’t want to hide behind a European form factor [of a rectangular bar]” he explained. “There are visual cues to signal that it might be different than a Hershey bar. We didn’t want people to be shocked when they ate it.”

Because for Taza, the chocolate is important, but it’s not everything. “The products we make are more of a call to action for the consumer,” Alex said. “You open it and eat it, and it makes you think, ‘Why is it like this?’” He’s hoping that the round chocolate bar with its grainy texture will open up a discussion about our food systems, that people will think not only about how the food tastes but also where it comes from, who made it, and how it got here. That’s why the company uses a direct trade model like Askinosie Chocolate (which I talked about last month) and publishes exactly where it gets its beans and how much they pay farmers. “We’re trying to lead the way and get other companies to step up their game so we can change the chocolate industry and the world in our own corner,” Alex said.

Since 2005, the company has skyrocketed to success. They have about 55 employees, and for fiscal year 2015, they’ll use 160 megatonnes of beans. You’ll find their bars everywhere from specialty shops to Whole Foods to the corner gas station. Sure, it’s good chocolate, but more than anything, Alex is a good businessman. After being inspired at his job at Zipcar, he knew he wanted to start a company that was “positive and in line with my values,” he said. “I was passionate about food, and market research showed chocolate was going to be a macro long-term growth area in the specialty foods industry.

“The successful bean-to-bar chocolate makers don’t make a product that they’re enamored with themselves,” he explained. “They make what the consumer wants. I’d love to make beautiful single-origin bars,” he continued. “But single-origin Madagascar chocolate bars don’t sell. If you want to go nationwide,” he continued, “you need to be selling flavored bars.”

That’s why Taza offers flavors like raspberry nib crunch, peppermint stick, and toffee almond sea salt, as well as chocolate-covered almonds, cashews, and hazelnuts (for the record, they also have a line of dark single-origin bars). When most makers were creating pure two-ingredient bars — just cacao and sugar — they were one of the first to go this direction. Now other makers are following suit, realizing that it doesn’t dilute the integrity of the chocolate to add high-end ingredients like salt, almonds, and sometimes even (gasp!) cocoa butter. But as Alex said, “It’s still early days for the craft chocolate movement,” and people (including makers!) have a lot to learn about it.

So what happens when he brings some of his chocolate down to the farmers in Central and South America? “They’ll eat our chocolate if I give them a piece,” he said. “But they'll usually melt it down and make it into a drink.”

Cornmeal Bread With Sesame, Pumpkin, and Cocoa Nibs

For centuries chocolate was a savory treat. The ancient Mesoamericans combined it with ingredients like cornmeal, chiles, and even achiote. This recipe from bread baker Rhonda Crosson (Epicerie Boulud, formerly Bouchon) honors that tradition, similar to how Taza honors the drinking-chocolate tradition with its new take on Mexican-style chocolate. The recipe uses historical elements in a new form: a hearty bread with plenty of chew that marries a Sicilian dough with the complexity of a mole and a deep yellow color from the durum flour. This one is more complicated than most recipes on Chocolate Noise, but the result is worth the effort!

THE DAY BEFORE

Corn-Cacao-Seed Mash

50 g stone-ground cornmeal

2 cups water

25 g cocoa nibs, cracked

40 g pumpkin seeds, toasted and cracked

25 g sesame seeds, toasted

50 g hot water

1. Mix cornmeal and water, raise to boil.

2. Cook 5 to 7 minutes.

3. Drain and refrigerate overnight. Should yield 150 to 200 g cooked mash.

4. Meanwhile mix cocoa nibs, pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds, and water and leave at room temperature overnight.

5. In the morning, incorporate the cocoa and seed mixture into the cooked mash.

Poolish(yeasted pre-ferment)

150 g cool water

1 g instant yeast

150 g all-purpose flour

1. Dissolve the yeast in the water.

2. Incorporate flour into the water-yeast mix until smooth.

3. Cover loosely and allow to ferment at room temperature overnight.

THE DAY OF

Soaked Raisins

130 g raisins

hot water

1. Cover the raisins with hot water for 10 minutes.

2. Drain and gently squeeze out excess water.

3. Reserve.

Bread Dough

420 g durum flour

250 g water

16 g salt

3 g instant yeast

300 g Poolish (see recipe above)

Corn-cacao-seed mash (see recipe above)

Soaked raisins (see recipe above)

1. Preheat oven to 500 degrees.

2. Add the durum flour, water, salt, instant yeast, and Poolish to the bowl of a stand mixer. Incorporate ingredients on slow speed until homogenous. Increase speed to medium and mix until a moderately strong dough is formed. You should be able to “pull a window.”

3. Return mixer to slow speed and incorporate the corn-cacao-seed mixture and the soaked raisins until evenly incorporated.

4. Put into a bowl, cover, and allow to ferment for 45 minutes.

5. After 45 minutes, turn the mixture. Do not aggressively punch or degas. Allow to ferment 45 minutes longer.

6. Shape into two batards and place on a greased baking sheet.

7. Bake for 15 minutes, then rotate the sheet 180 degrees in the oven.

8. Bake for 15 more minutes or until the loaves are rich and brown.

9. Cool for at least 45 minutes, then enjoy!