Fresco Chocolate: Why Geeks Make the Best Chocolate

Rob Anderson is a geek. So he makes chocolate for other geeks, or, more accurately, “people who really like chocolate and geek out about it.” What does he mean by that? If you change one step of the chocolate-making process, you change the taste of the resulting chocolate entirely. And Rob wants to show you exactly what that means. He roasts beans four different ways and conches chocolate four different ways to create totally unique bars that bring the eater into the factory with him to be part of the process. Oh, and did I mention that he built most of the machines he uses himself?

First, let’s talk terms. Most of us know about roasting cocoa beans, whether that’s done in a convection oven or, in Rob’s case, a modified commercial clothes drier (“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is perfect,’” he recalls upon finding it). But conching? What the heck is conching? After the beans are ground with sugar and sometimes cocoa butter, the resulting “liquor” (it’s nonalcoholic, sorry) can still be kind of grainy. Some makers, especially those making European-style chocolate, add an extra step in the chocolate-making process and put the liquor in a machine called a conche, which stirs, aerates, and heats it in a particular way to make it extra smooth and bring out the best flavors even further.

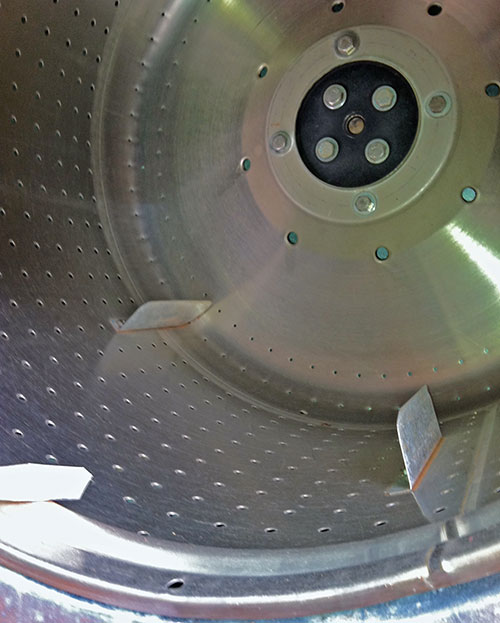

There many types of conches, and everyone has their own opinion about which is the best. Rob will tell you just about anything you want to know — unless it’s about his conche, which he built himself. That’s proprietary information. “I’ve done a lot of work in the technique of conching on a small scale,” he explained. “Being able to take a chocolate with a lot of aesthetics and volatiles and burn those volatiles off in a controlled way without diminishing the flavor. That’s my intellectual piece that keeps me apart from some other [makers].” He did send me a picture of an early version of his conche, though, and some veiled pictures of parts of his roaster (the conche is on the left, followed by the outside of the roaster in the middle and the inside of it on the right).

But long before Rob geeked out about chocolate, he was just an engineer who happened to wander into Scharffen Berger, in San Francisco. This was back around 2000, before the company was acquired by Hershey’s. He had never tasted such amazing chocolate. “It was kind of a revelation,” he recalls. Inspired by the first bean-to-bar maker in the country, he started looking into making chocolate himself. I figured, “Well, I’m an engineer, how hard could this be, right?” Famous last words.

He quickly realized that while there were industrial chocolate-making books, there was virtually no information about how to roast, grind, and conche chocolate on a small scale. In fact, he had to wheel and deal just to get a single bag of beans (i.e., not a literal ton of beans). And no amount of money would get him the machines he needed — because they didn’t exist. So “with my engineering background and [his business partner’s] fabrication background we actually built a roaster, winnower [which takes the shells off the beans], and a little conche.” Easy, right? Not exactly. Fifteen years later the roaster has gone through at least four iterations, the winnower over a dozen, the conch four. It turns out it’s actually pretty hard to make great chocolate.

Of course, just because you have a good machine doesn’t mean you can make good chocolate: It’s all about how you use those machines. And that’s where it gets even geekier. Rob roasts beans three different ways:

- Light, “just enough to soften raw cocoa’s acidic or green edge”

- Medium, “cocoa flavors develop to be balanced and flavorful”

- Dark, “full bodied, bold, intense, new flavor notes can develop while others may be subdued”

And he conches the chocolate liquor four different ways:

- None, “primitive, natural, pungent, not appropriate for all cocoa, exquisite for some”

- Subtle, “softens primitive edge while retaining aggressive flavor notes”

- Medium, “balance between aggressive and subdued, mellow”

- Long, “flavor peaks and valleys softened to a melodic harmony”

Most people make these decisions without you. They have a house style, and you can either take it or leave it. Rob gives you a choice. Do you want a dark roast and long conche like the Peru Marañon 230? A light roast and no conche like the Papua New Guinea 222? Or would you prefer a medium roast and medium conche like in the Dominican Republic 224 (which won a gold award at the 2015 International Chocolate Awards)?

He uses these semi-confusing tables to illustrate what’s going on in each bar:

Now, we haven’t even started to talk about where the cacao comes from. In other stories on Chocolate Noise, I’ve focused on single-origin chocolate, meaning it’s made with cacao from one specific place. Like with wine, cacao from a specific region has a specific taste: Madagascar’s can be fruity, Venezuela’s nutty. It’s called terroir, meaning the taste of the cacao is affected by the soil, landscape, and environment in which it’s grown. (Terroir also affects wine, coffee, tobacco, and even maple syrup, among other foods.)

Terroir is Rob’s next project. As predicted, he’s getting super geeky about it. Like most makers, he already lists the cacao’s country of origin and the year it was made into chocolate on his label. But now he’s comparing not only different countries but also different harvests. “I’ve got chocolate that is made with beans from one harvest year versus the second harvest year,” he told me recently. “I am going to be doing a compare and contrast with chocolate made exactly the same but with beans from two different harvest seasons.” So if it rained more one season than the next, for example, you’ll be able to taste the difference in your chocolate bar. As far as I know, no one has done an experiment quite like this before.

Here’s another reason Rob is different than the other makers I’ve profiled on Chocolate Noise: He has a day job, as a senior director of emerging technologies at an industrial electronics manufacturing company. That means he doesn’t feel the kind of pressure that other makers feel. “Fresco is an outlet for rest,” he said. “It’s something I super just enjoy doing. It’s a hobby that pays for itself.

“I don’t do the typical executive sort of things like play golf and hang out at the country club,” he continued. “I come home to make chocolate.”